We now know that on several occasions Indian

Thus, a person might say that they’re from the Naskapi First Nation of Kawawachikamach, or the Atikamekw First Nation of Manawan, or the Mohawk First Nation of Akwesasne, etc., identifying both the nation to which they belong and their place of origin or residence.

Indian Residential Schools: An Indispensable Tool for Assimilation

During an education conference, Marcelline Kanapé, who was principal of Uashkaikan Secondary School in Pessamit, summarized the essence of the Indian residential school system

The Indian residential school system was officially established in Canada in 1892. It was the result of agreements entered into between the Government of Canada and the Roman Catholic, Anglican, Methodist, and Presbyterian churches. The government terminated these agreements in 1969 (Aboriginal Healing Foundation 1999, 7).

The purpose of these establishments was simple: the evangelization and progressive assimilation

There are 11 Aboriginal nations recognized in Québec: Abenaki (Waban-Aki), Algonquin (Anishinabeg), Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok, Cree (Eeyou), Huron-Wendat, Inuit, Maliseet (Wolastoqiyik), Mi’gmaq (Micmac), Mohawk (Kanien’kehá:ka), Innu (Montagnais) and Naskapi. Across Canada, there are nearly sixty Aboriginal nations.

In 1931, there were 80 residential schools in Canada, located primarily in the Northwest and in the western provinces. For reasons that are not well understood, the system was established only later in Québec. Two Indian residential schools, one Catholic and the other Protestant, were established in Fort George before World War II. Four others were created after the war: Saint-Marc-de-Figuery, near Amos, Pointe-Bleue at Lac Saint-Jean, Maliotenam, near Sept-Îles, and La Tuque in Haute-Mauricie (ibid.).

The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples qualified the residential school episode as tragic. Moreover, since 1986, one by one the churches responsible for the residential schools have made public apologies. For decades, generations of children were knowingly removed from their parents and their villages, subjected to rigid discipline, and even prohibited from speaking their own languages under pain of punishment. During a televised interview about Indian residential schools, the former chief justice of the Supreme Court of Canada, Antonio Lamer, talked about kidnapping: [TRANSLATION] “For all practical purposes, we incarcerated them in schools. I am not very proud of that” (Réseau Historia May 2001). The history of residential schools is also marked by countless tales of negligence, abuse and physical and sexual violence. Although we should not assume that every school was the same, the findings are nevertheless serious. In 1998, the Government of Canada agreed to contribute $350 million to support community

In 2006, following a class action brought by former students of Indian residential schools against the Government of Canada and various religious groups, a court approved the largest class action settlement in Canadian history. Under the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, former students were paid general compensation, with higher payments being awarded to “students who suffered sexual and serious physical abuse, as well as other wrongful acts which have caused serious psychological consequences” (Walker, 2009). But more important still, the agreement called for the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, which was given the mandate to, among other things, document the truth and acknowledge residential school experiences, impacts and consequences and pave the way to reconciliation. Between 2008 and 2015, the members of the Commission travelled to all parts of Canada and heard from more than 6750 witnesses, survivors of residential schools, members of their families and other individuals who wished to share their knowledge of the residential school system and its legacy. In its report released in 2015, this Commission described the residential school episode as a “cultural genocide” and made 94 recommendations or calls for action (Canada. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015a and b).

Il est important de mentionner qu’en juin 2008, le premier ministre du Canada avait présenté ses excuses au nom du It is important to mention that, in June 2008, the Prime Minister of Canada offered, on behalf of the Government of Canada, a formal apology to Aboriginal peoples for the suffering that resulted from assimilative, government-sanctioned residential schools. The text of the apology reiterated the objectives of the residential school system:

…to remove and isolate children from the influence of their homes, families, traditions and cultures, and to assimilate them into the dominant culture. These objectives were based on the assumption that aboriginal cultures and spiritual beliefs were inferior.

The legacy of the Indian residential schools policy has had a damaging impact on First Nations and Inuit communities. The numerous reports on the subject all contain the same findings, that is, that the legacy of the residential schools has contributed to the social problems that exist today in these communities.

At the First Nations Socioeconomic Forum held in the community of Mashteuiatsh in the Lac St-Jean region in October 2006, Thaddée André, then chief of Matimekush, summed up in one powerful sentence how the assimilative residential school policy had affected his life: [TRANSLATION] “All my life, I wanted to be white.” He added, “But I wasn’t happy.”

Photo credit: Institut Tshakapesh, fonds Père Jean Fortin

Photo credit: Collection of Jean-Claude Therrien-Pinette

At the same time, in response to land claims in British Columbia, the federal government amended the Indian Act (Daugherty 1982, 16) so that, from 1927 to 1951, any fundraising destined for land-claims proceedings constituted an offence. The Indian communities were trapped, deprived of any legal recourse.

In 1945, members of First Nations that attempted to affirm their sovereignty and their desire for self-government

These few historical events are essential to a better understanding of the real nature of the Indian Act and federal guardianship

Within the context of the Indian Act, the concept of guardianship takes on a unique meaning as it applies not only to individuals but also to entire communities. The lawyer Renée Dupuis, author of a book on First Nations issues in Canada, summarizes this guardianship regime well: “Revised in 1951, the federal Act clearly constitutes a regime of guardianship of Indians (both individually and collectively) and of the lands reserved for them. Actually, the Indians have a status equivalent to that of a minor child, since they are subject to the control of the government, which has the authority to make decisions on their behalf. All aspects of the lives of individuals and communities are supervised, from an Indian’s birth to his death, from the creation of a band to the cessation of a reserve.”

Note that several First Nations in Canada, including the Cree and Naskapi nations in Québec, are no longer subject to the Indian Act.

Obtaining the Right to Vote

Québec was the last province to grant voting rights to First Nations peoples. At the federal level, partial voting rights had been granted in 1885 and withdrawn in 1896. Hence, Native persons in Ontario, Québec and the Maritimes were eligible to vote in the 1887, 1891 and 1896 general elections. The right to vote was withdrawn because it was deemed incompatible with the status of guardianship. Persons under guardianship, such as Indians, were not considered to be subjects by right (nor were women). Consequently, they were not entitled to the responsibility of voting (Jamieson 1978; see also Hawthorn and Tremblay 1966, I: chap. XIII).

However, exercising the right to vote was a controversial subject even in Aboriginal communities. Several communities considered that voting constituted an acceptance of Canadian citizenship and a renunciation of their right to be sovereign, independent peoples:

For example, in 1963, a circular distributed in Saint-Régis (Akwesasne) regarding an Ontario provincial election clearly illustrated the significance of refusing the right to vote. It stated that if Indians voted, they would no longer constitute a sovereign nation, since they would become Canadian and British subjects by that very fact. Moreover, the “Redskin” was morally bound not to vote in federal or provincial elections. Finally, the circular stated that a band of irresponsible Redskins, suffering from a racial inferiority complex, reported to the polling booths and unfortunately forever renounced their national sovereignty and identity!

Even today, several nations still deliberately do not exercise their voting rights in federal and provincial elections. The situation is different for the Inuit, who were explicitly excluded from the Indian Act, as we will see in Chapter 4. They gained the right to vote in federal elections in 1950, whereas First Nations people did not receive the same right until 10 years later.

Right to Vote

Nova Scotia

Always

Newfoundland

Always

Northwest Territories

Always

British Columbia

1949

Manitoba

1952

Ontario

1954

Canada

1960

Saskatchewan

1960

Yukon

1960

New Brunswick

1963

Prince Edward Island

1963

Alberta

1965

Québec

1969

Source: Source: Hawthorn and Tremblay 1966, I; Canada 1980

The Tuberculosis Epidemic of the Mid-50s

One Inuk Out of Seven in Southern Hospitals

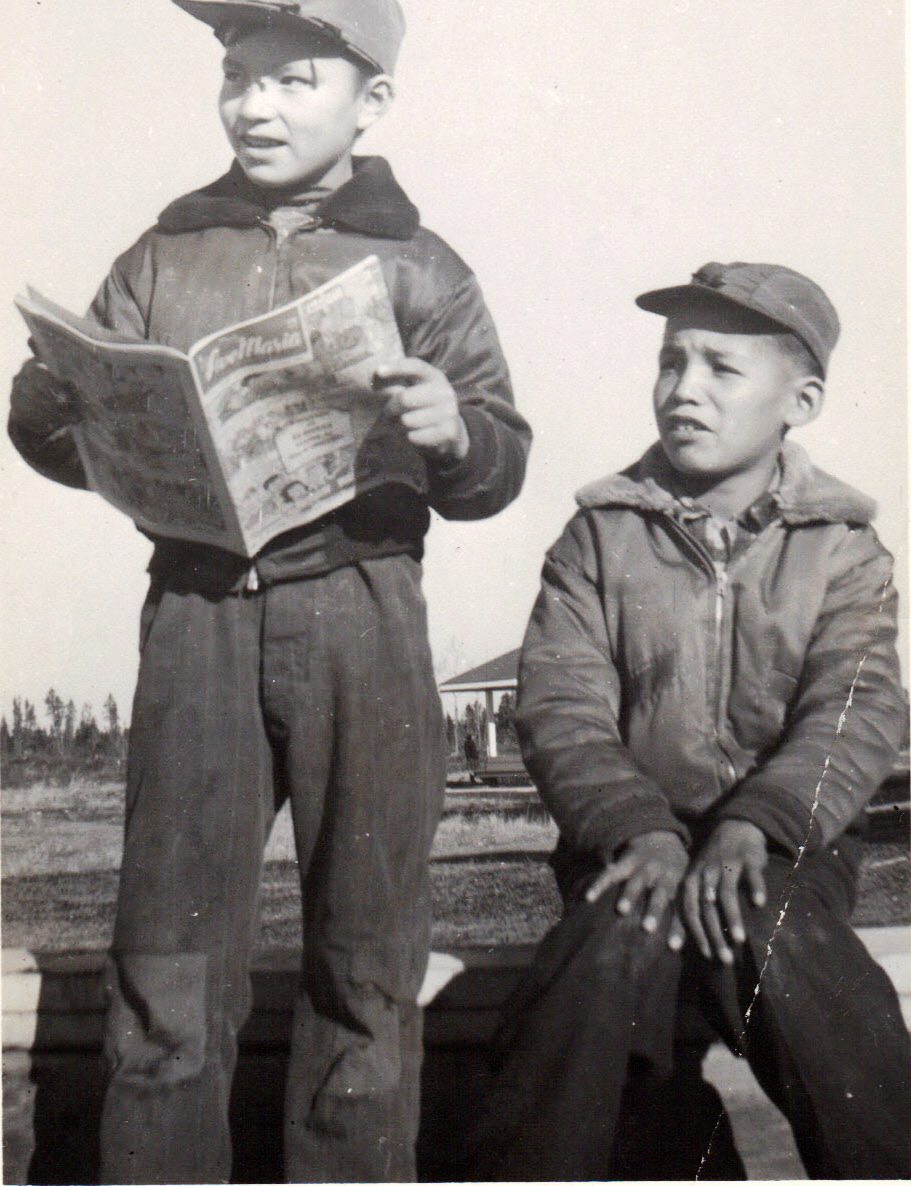

In the mid-50s, tuberculosis ravaged northern communities. These two photographs were taken in December 1956 at Immigration Hospital (today Christ-Roi Hospital), near Québec City. This hospital was used because Indian Affairs and Northern Development was under the jurisdiction of the Department of Citizenship and Immigration between 1949 and 1965. In the first photograph, a group of Inuit women and children; below right, in front of the Christmas tree, is a group of young Innus from the Sept-Îles region.

In his book A History of the Original Peoples of Northern Canada (1974), Keith Crowe states that in 1950, one Inuk out of five had tuberculosis; “in 1956, one Inuk out of seven was hospitalized in the South and someone in practically every First Nations family had to be evacuated to the South for months or years.”

Crowe reports “that every year medical teams went to the North, taking advantage of treaty

In Canada, there are two types of treaties with Indigenous peoples: peace and friendship treaties, and land treaties, i.e., those specifically dealing with land and land titles.

The government’s objective with land treaties was to remove obstacles to colonization and to encourage First Nations members to abandon their lands and lifestyles and assimilate.

In particular, the author evokes this sad period when children and parents were evacuated to southern hospitals, and how this upset so many families. Tuberculosis victims returned home handicapped and could no longer hunt.

Patients were “lost” for years because of administrative errors. Children forgot their mother tongue and were unable to communicate with their peers on their return. Finally, patients had difficulty reintegrating into communities “after spending years in overheated hospitals, virtually without exercise, in incessant cleanliness, and eating pre-prepared food” (Crowe 1979, 161, 215 and 216).

The degree of trauma suffered by the First Nations people and numerous Inuit who were hospitalized in the south during that time was brought to the public’s attention in 2008 through the beautiful film Ce qu’il faut pour vivre (The Necessities of Life). Directed by Benoît Pilon, based on a screenplay by Bernard Émond, it tells the story of an Inuit hunter with tuberculosis in the 1950s. The hit of the year in Québec movies, the film won numerous national and international awards. Natar Ungalaak, who played the Inuit hunter, won the Jutra Award for Best Actor in 2009.